An Obsession with Heads. The Impact of African Arts… | by Cleveland Museum of Art | CMA Thinker | May, 2022

10 min read [ad_1]

The Impact of African Arts, Anthropology, and Photography on the Works of Alberto Giacometti

By Kristen Windmuller-Luna, Curator of African Arts

Sometimes when I walk through the CMA’s galleries, I see someone with a sketchbook drawing a sculpture. What is lost — and what is gained — as they translate its three dimensions into two, moving the work from pedestal to paper? I’ve also spent a lot of time drawing in museums, to appreciate and understand art. Like myself and my fellow museum sketchers, Alberto Giacometti drew from great artworks to learn and to work through his own ideas. Though an avid museum goer, Giacometti based most of his sketches of African arts on photographic reproductions in books linked to the entangled networks of colonialism, ethnographic museums, and the discipline of anthropology. By using photographs — rather than actual artworks — as his main source material, Giacometti performed artistic and theoretical translations of African arts.

Personal Perspectives, European Perceptions

Alberto Giacometti continually engaged with African artists’ creations from his early career through his later model-based work of the 1940s through 1960s, which is the time frame in focus for the featured exhibition Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure. He didn’t seek to understand their aesthetic perspectives or their works’ meaning. Instead, what compelled him was a personal interpretation of African arts as reality-revealing archetypes:

Any of us resembles much more an Egyptian sculpture than any other sculpture ever made. And it’s the same thing for exotic arts, for African or Oceanic sculpture. People like them because they think them entirely invented, and because they refute the outside world, the common view on reality…Style gives us the most accurate vision.[1]

The earliest sculptures he created in Paris drew from African artworks that he viewed in ethnographic museums or in personal collections. These displays were the direct result of European colonial conquest and exploration across Africa. Brought to Europe by the thousands since the 1870s in violent, bureaucratic, or even mundane ways, African artworks and weapons were often displayed to shore up racist conceptions of savagery or primitiveness. First influenced by colonial geography, Western definitions of “art” further refined the “African art canon” to favor wooden sculptures or masks from Western and Central Africa.

The impact of this narrow “African art canon” is seen in 1927’s Spoon Woman and The Couple, as is Giacometti’s tendency to select elements and interpretations of African artworks. Scholars have linked Spoon Woman’s scoop-like form to an oversized ceremonial ladle that Dan communities in Côte d’Ivoire once honored a generous woman with during festivals.

The pointed oval-shaped woman in The Couple suggests a shield, like this Ugandan example, or a Kota-style mbulu ngulu sculpture from Gabon (on view in gallery 108). Set atop containers of relics (bones), these guardian figures helped people connect with their ancestors through prayer. Giacometti owned an mbulu ngulu similar to the one now at the CMA; both share their shape, proportions, and parallel cheek strips with The Couple’s female figure. Unlike his artistic peers in Paris, such as Pablo Picasso, Giacometti focused his collecting efforts on books rather than artworks: many of these are linked to his drawing and sculpture practices.

Sketching from Books

While he often spoke or wrote about trips to the Louvre and the Trocadéro Ethnographic Museum to see Egyptian or sub-Saharan African art, books had fueled Giacometti’s appetite for copy-sketching since childhood: “I see myself…returning later in the evening to my studio in Paris, leafing through books and copying this or that Egyptian sculpture…”[2]

Through his book collection, Giacometti became acquainted with artworks made in places he never visited. He based many of his sketches of African artworks on photographic illustrations from art, anthropology, ethnography, and Surrealist publications. He often couldn’t read the accompanying texts, as he primarily knew Italian and French. Focused on appearances and links with modern European art, many of his favorite books were for art lovers, not scholars, such as art historian Hedwig Fechheimer’s illustrated German volumes on pharaonic Egypt. Art from Egypt’s Amarna period (Dynasty 18) particularly filled Giacometti’s sketchbooks. Like the tradition-shattering European Surrealist movement, the Amarna style rapidly shifted pharaonic Egyptian art. Two works in gallery 107 show how Amarna-st

yle artists elongated the body and depicted its movement in response to the religious reforms of Pharaoh Akhenaten (reigned 1351–1334 BC).

A profile portrait of Queen Nefertiti blends realistic and stylized elements, juxtaposing her narrowed eyes and pointed facial features with her curved neck and the rounded mass of her hair (or wig). Similar contrasts echo in Giacometti’s small busts and portrait heads like Bust of Annette VIII. In a painted Amarna-style stone relief, a male figure steps forward on slender feet. Giacometti duplicated this inverted V-stance in his copy-sketches of Egyptian art, later reinterpreting it in his Walking Woman sculptures of the 1930s and the Walking Man series of the 1950s and 1960s.

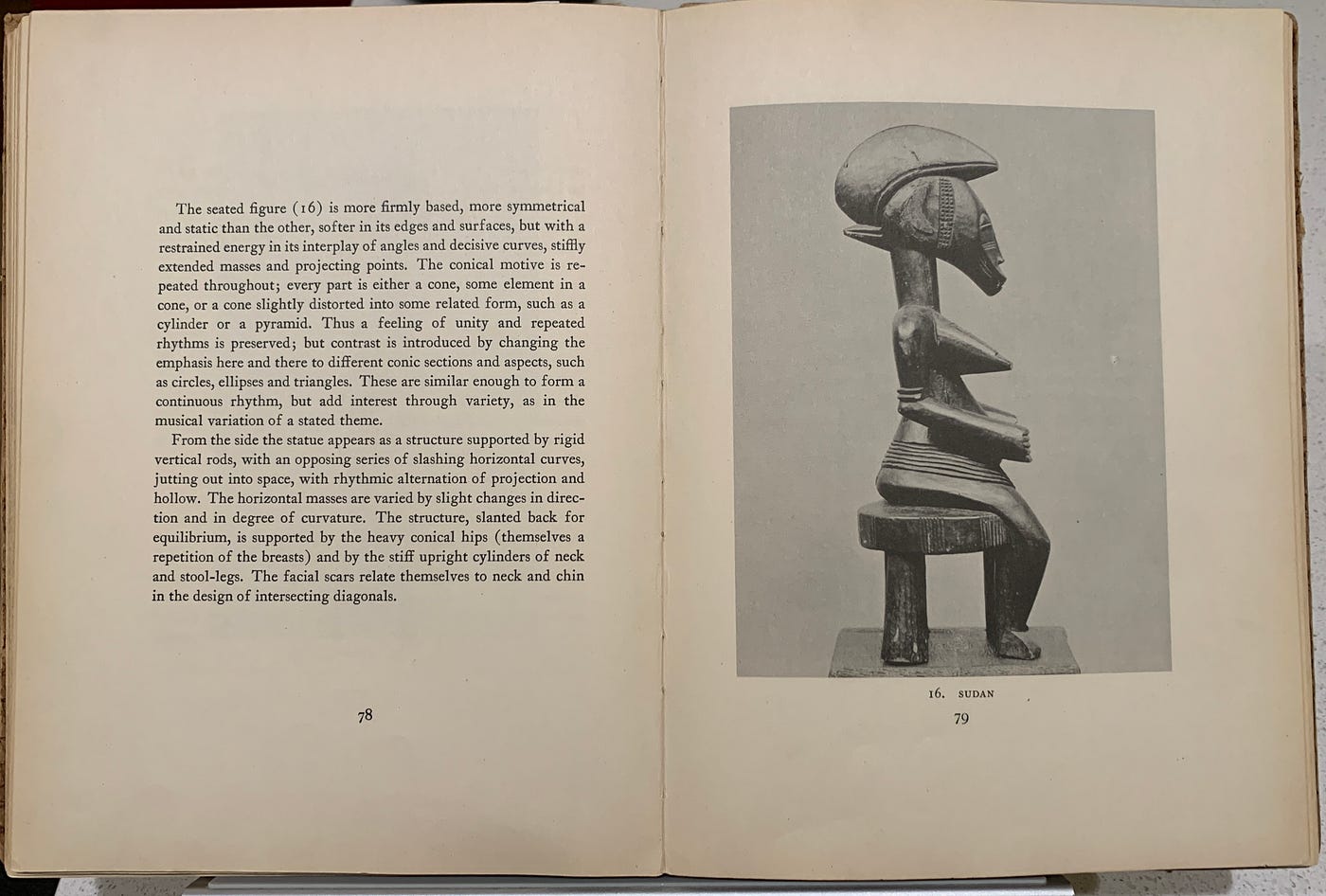

The illustrations in publications by members of his social circle further transformed African arts into icons for Giacometti to interpret. These included “primitive” or “tribal” art books by art dealer Paul Guillaume (along with CMA art educator Thomas Munro), art historian Carl Einstein, and writer-ethnographer Michel Leiris. A member of France’s Dakar-Djibouti Expedition (a colonial collecting and ethnography expedition between 1931 and 1933), Leiris frequently contributed to the Surrealist publication Minotaure. His photo-essays on masks from French Sudan (now Mali and Burkina Faso) included a satimbe mask similar to one now in Cleveland. Once worn with a costume, it was performed during a Dogon community’s post-funeral dama rite.

Satimbe masks honor the mythical female discoverer of Dogon masks, as well as the Yasigne (“sisters of the mask”) who take part in the dama rite’s otherwise male activities. Perched atop the rectangular face mask, a female figure raises her arms skyward toward Amma, the creator god. Her full breasts, slender waist, and heavy hips symbolize fertility. However, Leiris transformed these meaningful masks into clip art–like icons by illustrating them as cut-outs or silhouettes. When viewed this way, the satimbe mask becomes a sculpture of a thin-limbed, curvy woman on a blocky base, much like Giacometti’s later bronzes.

Imposing Ways of Seeing and Knowing through Photography

I suggest that by using photographs of African artworks as sources, Giacometti engaged in visual translations across media and dimensions that affected the appearance of his own creations. In the exhibition’s catalogue, Romain Perrin writes that “Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures not only impose on the spectator a certain way of looking, because their scale is no longer connected with their environment, but they also show the result of the artist’s direct perception.”[3] Giacometti’s engagement with African arts in European museums and books — and the ways of looking and understanding they imposed upon viewers — can be similarly described.

When Giacometti leafed through books to find artworks to copy, the African pieces he encountered were highly filtered, their geography, format, and appearance selected or altered because of European preferences. In the early twentieth century, photographers shot African artworks to satisfy European interest in forms. From lighting to staging to printing, photographic techniques changed the appearance of sculptures and face masks by downplaying textures, eliminating colors, and erasing traces of the artistic process, like tool marks. Tightly cropped front, side, and three-quarter views made objects “float” before plain backdrops. Inexpensive photographic printing processes used for art books and magazines (like photogravure, collotype, and aquatone) produced

matte images whose velvety, low-contrast tones made their subjects appear dull and flat. Scaling works as if they were the same height further invited viewers to compare them on a one-to-one basis as uniform examples of “African arts.” This standardized way of photographing African objects and artworks was linked to anthropological photographs.

Anthropologists believed photography was a neutral document for studying and recording humanity. In practice, however, both photography and anthropology carried biases from colonialism and social Darwinism, which aimed to demonstrate the inferiority of non-white peoples. Euro-American anthropologists used anthropometric photography systems whose technical specifications included nude subjects, side and frontal poses, head close-ups, and blank backgrounds. Early twentieth-century photographs of African objects adhered to these same formats and goals, including details of heads and nude subjects (sculptures and masks stripped bare of their attachments to reveal their sculptural “essence”).

The resulting photographs and publications converted an artist’s unique creation into a type (such as “Dogon mask”), just as anthropometric photographs made individuals representative of an entire ethnicity (such as “Dogon man”).[4]

Translating across Dimensions

Giacometti’s unusual way of rendering the human body as flattened, colorless, and elongated reflects how he viewed African artists’ rendering of the body as depicted and transformed through the lenses of European photographers. Studying photographs of African arts prompted him to make visual translations that affected his sculptural practice and possibly encouraged his near-obsessive focus on the human form and head. Echoing anthropometric-style photographs of African individuals and sculptures, many of his later drawings and sculptures (especially those called “Man” or “Woman”) depicted unclothed, hairless bodies or heads in frontal or side views. When drawing, Giacometti preserved photography’s transformation of three-dimensional African sculptures into two dimensions and from color to black and white. He then reversed it when sculpting; like a visual version of the “telephone” game, he altered African artists’ works through this process and imposed his own way of seeing. Doubling and reflecting the underlying colonial and anthropological contexts of the photographs he used as source material, his artworks held their own meaning, yet could never be completely true to the original.

Sketching in a museum or drawing from an art book today is a very different experience than the one Giacometti had decades ago. We have new methods for art history, collecting, and museum photography, and more context — from gallery labels and books to audio guides and apps — than he ever could have imagined. Yet in many ways, the human experience of drawing to see, learn, interpret, and understand remains the same: an impulse to translate works of the past between mediums and through the lens of our own experiences and times with the help of pencil and pad.

Draw on these new connections and during your visit to view Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure through June 12, 2022. Members see it FREE.

Recommended Reading

Grenier, Catherine, and Serena Bucalo-Mussely. Alberto Giacometti: Rétrospective. Rabat: Fondation Nationale des Musées and Musée Mohammed VI d’art moderne et contemporain; Paris: Fondation Giacometti, 2016.

Grossman, Wendy. Man Ray, African Art, and the Modernist Lens. Minneapolis; University of Minnesota Press; Washington, DC: International Arts and Artists, 2009.

Pautot, Thierry, Romain Perrin, and Marc Étienne, M. Alberto Giacometti et l’Égypte antique. Exh. cat. Lyon: Fage éditions; Paris: Fondation Giacometti-Institut, 2021.

Pinney, Christopher. Photography and Anthropology. London; Reaktion Books, 2012.

References

[1] Alberto Giacometti, quoted in Pierre Schneider, “Au Louvre avec Alberto Giacometti,” Preuves, no. 139 (September 1962): 23–30; reprinted in Giacometti, Notes on the Copies (Paris: Hermann and Fondation Giacometti, 2021), 19.

[2] Alberto Giacometti, quoted in Véronique Wiesinger, Alberto Giacometti: les copies du passé (Lyon: Fage éditions; Paris: Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti, 2012), 47 (my translation).

[3] Émilie Bouvard, ed. Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure (Cleveland: Cleveland Museum of Art / Yale University Press, 2022), 148.

[4] Anthropometric photographs are not displayed here because they were frequently taken without the full or freely given consent of their subjects.

Alberto Giacometti: Toward the Ultimate Figure is co-organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Fondation Giacometti.

Generous support is provided in memory of Helen M. DeGulis, by Malcolm Kenney, Mr. and Mrs. Frank H. Porter Jr., and the Simon Family Foundation, a supporting foundation of the Jewish Federation of Cleveland.

All exhibitions at the Cleveland Museum of Art are underwritten by the CMA Fund for Exhibitions. Generous annual support is provided by an anonymous supporter, Dick Blum (deceased) and Harriet Warm, Dr. Ben H. and Julia Brouhard, Mr. and Mrs. Walter R. Chapman Jr., the Jeffery Wallace Ellis Trust in memory of Lloyd H. Ellis Jr., Leigh and Andy Fabens, Michael Frank in memory of Patricia Snyder, the Sam J. Frankino Foundation, Janice Hammond and Edward Hemmelgarn, Eva and Rudolf Linnebach, William S. and Margaret F. Lipscomb, Bill and Joyce Litzler, Tim O’Brien and Breck Platner, Anne H. Weil, the Womens Council of the Cleveland Museum of Art, and Claudia C. Woods and David A. Osage.

[ad_2]

Source link